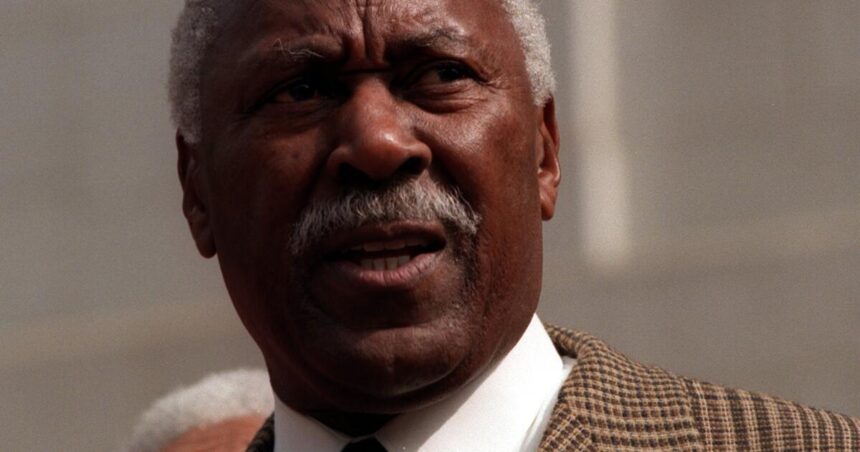

The former member of the Council of the City of Los Angeles, Nathaniel “Nate”, always spoke with a sense of security and a firm belief in his own destiny.

It was the type of conviction that Tok for a black man born in Macon, Georgia, in 1929 ascending to the highest ranges of political power in Los Angeles, representing the region as a state senator and then serving in the city’s counter.

Holden, an imposing figure in the political sand of Los Angeles, died on Wednesday at age 95, his family told the County Supervisor, Janice Hahn.

“Nate Holden was a legend here in Los Angeles,” Hahn said in a statement. “He was a lion in the state Senate and a force to take into account at the counter of the city of Los Angeles. I learned a lot sitting next to the cameras as a new countermamar.”

Before launching his political career, Holden served as Hahn’s father’s assistant, the former Kenneth Hahn County Supervisor, who trusted Holden for his “unique brand of wisdom.” The young Hahn said he referred to him as Uncle Nate and considered that Holden was part of the family.

Holden was a 6 -year -old boy in Georgia, he said, Hed listened to the state governor on the radio promising to continue his mission of suppressing blacks, who at that time were the most basic human rights and were frequent objectives of angry white turbs.

They remembered their childhood challenge for racism that was later on display in the deep south. Rocks would arrive at local public pools on the days when white people were allowed to use them, and once he told a white couple while cleaning his backyard that he intended to become president of the United States.

His father was a Brakeman of the Central Railway Company of Georgia, and when his parents separated when he was 10 years old, Sate moved with his mother and his brothers to Elizabeth, NJ, where his grandmother lived.

He was a rookie boxer at age 16, eliminating experienced competitors and local champions in his New Jersey gym. In 1946, the song about his age and joined the US Army. UU. He was deployed in Germany after World War II, where he served as a military police officer.

When Holden returned to the United States, he decided to become a fool. But, he said, one of his teachers cools on purpose a bad qualification to discourage him, telling that this work was beyond the reach of a black man.

When he requested a training program for military veterans, he was denied again and told him that he was wasting time, that he would never take a job.

“I served God and the country, I will enter that training program,” he said he told them. “If I don’t understand, I’m going to Washington and call that president.”

He was finally admitted and studying design and engineering at night while ending high school. Hey Pose worked for several aerospace companies, which led him to California.

Holden made his first foray into politics as a member of the Democratic Council of California, a reform of trend reform to the left. He lost an offer for Congress after campaigning as an opponent of the Vietnam War, but also became president of the Democratic Reform Group.

After being chosen for the Senate of California in 1974, it helped the Write Financial Housing Discrimination Law, which prohibits financial institutions from being a lack of race, religion, sex or marital status. He also defended the legislation to demand from California public schools to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr.

Holden left the state Senate after a period to run again for Congress, losing once more. In 1971, he became a assistant deputy director of the Los Angeles County Supervisor, Kenneth Hahn, a popular white politician in a black district.

By the time he returned his view to the Council of the City of Los Angeles in 1987, he had lost six of seven political campaigns of about two decades.

“I don’t think I lost a race,” the Times celebrated in 1987. “Maybe I was not chosen, but I did the race. And every time I ran a race, I think the community benefited.”

Holden enjoyed the political struggle, often at the expense of his colleagues.

“There is nothing wrong with the competition,” he told the Times in 1987. “It’s like boxing. If you get up in that ring and you’re there alone, you’re just in the shadow. It’s always good to have a contest. There is nothing wrong.”

Duration The possession of almost two decades of Holden in the City Council of Los Angeles, developed a reputation as a lonely wolf and, as sometimes difficult, abrasive, vindictive and participant in a great policy. He frequently voted against the rest of the counter in unpleasant votes and openly called his “stupid”, “false” and “lazy” colleagues.

In the council, Milke Flores told the Times in 1989 that once he saw the name of all those who were against him in a counter of the city and then approached each person in his list to remind them that he would not forget the vote.

“I’m not directing any nursery school,” he said. “I ask difficult questions of bureaucrats. Hello, politics is a difficult business.”

When the Council was forced by mandate limits in 2003, the Times columnist, Patt Morrison, said it would lose it “a 16 -year -old franchise on indignation snacks, showbaking and chutzpah.”

However, among the constituents, Holden was hotly accepted as an opponent of the political establishment and a champion of his community.

Holden represented the 10 predominantly black district and became a spokesman for the poor and middle class in the southern and southwest center of Los Angeles, where the neighborhoods fought with drug and gang violence at the end of the 1980s. He worked for written funds for an increase in police feet patrols to reduce crime and encourage a more reliable relationship between officers and residents.

The constantly made slope lists solutions, tree cuts, broken street lamps and municipal departments with letters and phone calls so that the work continues. He became legendary among the city’s employees to rebuke them when things did not happen quick enough.

“They used to call me stop signs,” because I made my district safe for pedestrians, “he said.” When something had to be done, I did it. “

He also pressed for more parks, libraries and recreational centers in his district and was so interested in neighborhoods that when a doctor center was built in the center of 2003, he was appointed in honor of Holden.

“Nate works harder with his constituents and other Los Angeles residents than to please his colleagues,” said Joy Picus, the then Counter member, to The Times in 1993. “He has street intelligence and is very populist.”

Always looking for a fight, Holden made a pass in the mayor post in 1989 against the very favored headline, Tom Bradley, who had previously represented the tenth district as a counter member.

Holden gave the duration of the national news the campaign when he launched a weapons repurchase at that time, offering $ 300 of his own campaign war chest to anyone who delivers an assault rifle.

Holden lost, but his intense campaign combined with a low electoral participation of Bradley, a race for his money.

“He is a fighter,” said Herb Wesson, who worked as Holden Personnel Head of his first term. “If I was ever in a bar fight, I hope Nate was in the stool by my side.”

The long period of Holden in the City Council was cemented in part by its courtship or the American Korean components. Althegh Koreatown residents did not have a large voting block, had fund collection power, donating a quarter of the campaign contributions that Holden received from 1991 to 1994.

In return, they helped US business owners acquire liquor permits in Los Angeles, turning the area into one of the city’s hot points for nightlife after companies hesitated with an economic fall in the early 1990s.

“That’s Nate Holden’s Legacy in Koreatown,” Charles Kim, Executive Director of the Korean American Coalition, Toled The Times in 2002. EXTENDING ESIRS AND EXTENDING ESIR AND EXTENDING ESIR AND EXTENDING THES AND EXTENDING ESIR AND EXTENGING EMS AND EXTENDING EMLING AND EXTENGING OF THEIR “AND THE EXTENSION OF THE YOURS AND THE EXTENSION OF YOU

A Times research report later revealed that many of the business owners who received liquor licenses had donated to Holden’s campaigns. And some saw duplicity in Holden’s efforts since the councilor had fought so strongly to restrict liquor licenses in southern Los Angeles after the 1992 disturbances.

Outside of politics, Holden’s tenacity was obvious in other ways, such as the Los Angeles Marathon, which extended to 61 and again 62. When he went to a seat of the assembly after his career ended, the campaign when marching dancing-devas of dance and you and alte

“I used to run everything in the snow in New Jersey. Cold sky. Before school every morning ran,” he said. “When I came to California, I ran every morning – 5 am”

Holden’s long career, however, was not exempt from imperfections. In the 1990s, Holden was beaten with three accusations of sexual harassment separated from the previous AIDS. The women accused him of inappropriate and offensive comments and created a hostile work environment.

Holden defended himself aggressively, won a case in court and resolved another. A third claim was eliminated. But his legal defense cost the city approximately $ 1.3 million.

It was also repeatedly advanced for violating the financing laws of the campaign, accumulating more than 70 violations and $ 30,000 in fines. Holden recognized some of the violations, but claimed that the city’s ethics commission kept him in a higher standard than his colleagues.

Holden retired from the Council in 2003, but remained active in the community. At 92, I was still serving at the Board of the District of Air Quality Management of the South Coast, a regulatory agency that excessive air quality for much of Los Angeles and the Inner Empire.

Reflecting on his legacy, he said he wanted to be remembered as “a good guy.”

“Do my best for people. Law and order. Make sure people’s communities are safe. I did everything,” he said.

Holden is survived by the children Reginald Holden, former deputy of the Sheriff of the Los Angeles County, and Chris Holden, former member of the California Assembly and former mayor of Pasadena, as well as several grandchildren. His wife, Fannie Louise Holden, died in 2013 due to complications of Alzheimer’s disease.

The Times staff writer, Clara Harter, contributed to this report.